I still remember the OG Blob—that 1958 sci-fi flick where an alien oozes its way across Earth, devouring everything in sight. And when meteorologists started using that name for a real weather pattern in the Pacific? Yeah… it was just as terrifying, at least for us snow lovers. The last time this beast showed up it was over the course of multiple seasons. Spoiler alert: it was a nightmare for skiers and snowboarders. Now it’s back. Will it stick around? Too early to say. But let’s take a quick trip down memory lane and see what the original “Blob” winter looked like, and what it might mean for us this season. Huge thanks to Tony Crocker for allowing us to use his information to give us a glimpse at these past winters.

Beyond El Niño & La Niña – Meet “The Blob”

We all know El Niño and La Niña can seriously mess with how much snow our favorite ski resorts get. But back in the summer of 2013, a new term slid into the ski weather lexicon: “The Blob.”

Meteorologists coined the term to describe a massive marine heatwave in the northeastern Pacific. This is when ocean water temps soared way above normal. A stubborn high-pressure system parked itself over the region, calming the surface winds. With weaker winds, there was less evaporation and mixing of deeper, cooler water — basically creating a hot tub effect in the ocean.

Battle of the Blobs – Who Won?

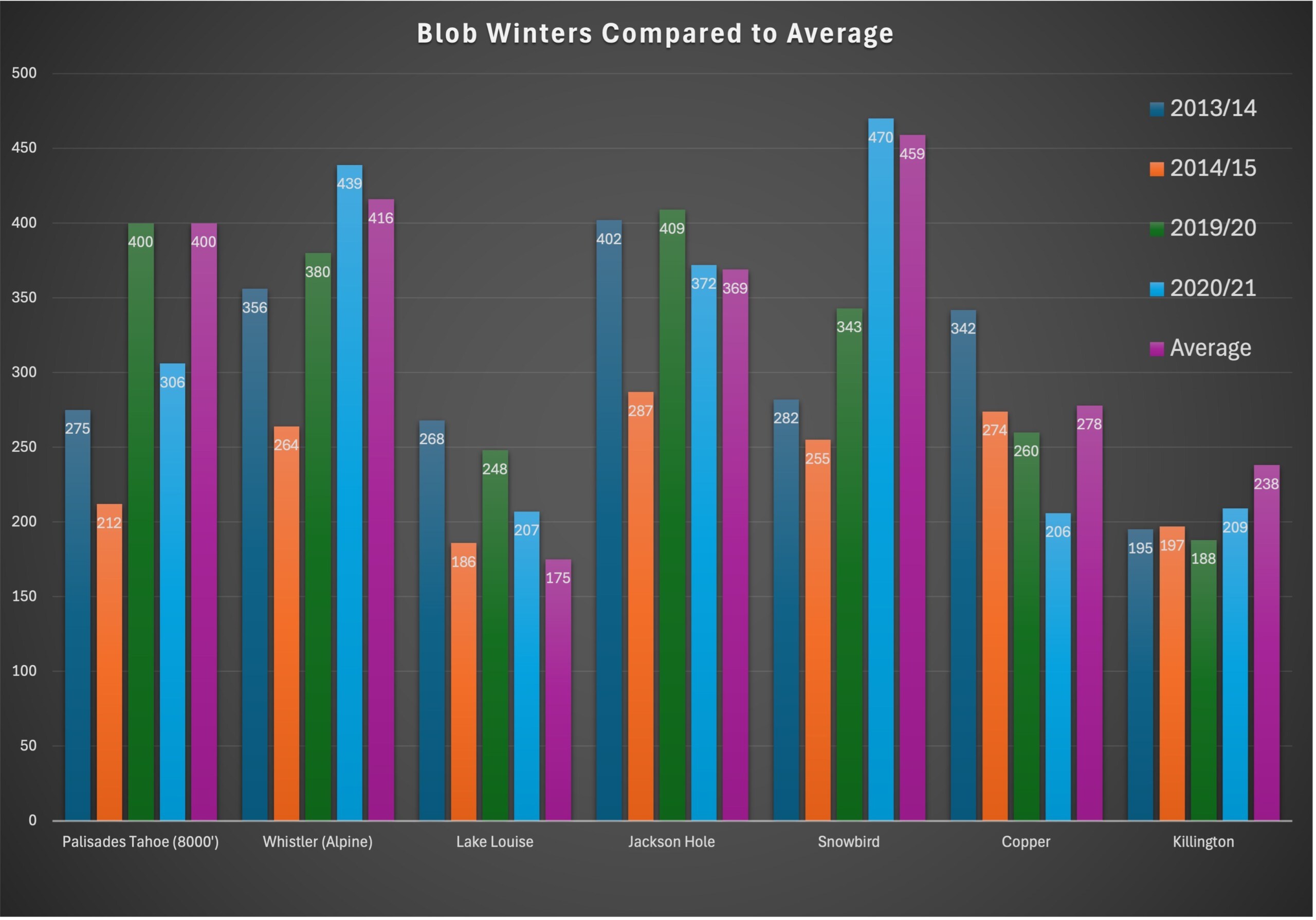

The first Blob hit during the 2013/14 and 2014/15 seasons, and then Blob 2.0 made an unwanted comeback in the summer of 2019, throwing a wrench into the 2019/20 and 2020/21 winters. As you can see in the chart below, some winters everyone got hosed. Others? Not as bad. The regions that weathered these seasons the best were the Canadian Rockies and northern Rockies.

Blob 3.0 – Is it THAT Bad?

As Lake Tahoe’s go-to forecaster Bryan Allegretto put it: “I hate to be the bearer of bad news… we may be in for a fairly dry and mild winter.” But it’s not just about how much snow falls—it’s how it falls. Did it all dump in one crazy month? Were the storms warm, rolling in on a Pineapple Express, or cold and dry from an Alaskan low?

Let’s break down how the original Blob seasons played out across each region. If history tells us anything, it’s to expect a wild ride. Just remember—even the worst winters have their epic days, like the one captured in this shot from the 2019/20 season.

2013/14 Ski Season

West Coast (California & Pacific Northwest):

Snow levels told the real story of the winter—like at Palisades, where 263″ fell at 8,000 feet but only 90″ at the base. The season started dry, with just a brief tease in mid-January before finally turning on in late January through mid-February. The Sierra picked up 3–5 feet, and NorCal saw a decent rebound with March bookend storms. The Pacific Northwest went from famine to feast in February, stacking over 7 feet in just a few weeks and staying active into spring.

Rockies (Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana):

Much of the central Rockies hovered around average into December. Then came a serious dry spell in mid-January, even in Colorado’s snowiest zones along I-70, which struggled to pick up more than a foot during the second half of the month. Things flipped in late January into February with the most widespread snow cycle of the season, hitting Utah and Colorado hard. Spring became the real standout for the Front Range and I-70 corridor. April and May saw consistent, above-average snowfall that kept the stoke alive long after other areas had tapped out.

Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, Southern Utah):

The Southwest was surprisingly strong early in the season, catching some of the best storms in North America by late fall. But after that early bounty, the tap shut off. January through March saw minimal activity compared to the rest of the West. While other regions caught rebounds, the Southwest was consistently left on the sidelines—making it one of the driest spots overall by season’s end.

Western Canada

The Canadian Rockies were one of the season’s big winners. Snowfall was heavy right from the start and stayed strong through December. February and March continued to deliver with deep storms, especially in British Columbia. Western Canada saw some of the most consistent and heavy snow throughout the entire season, making it a go-to destination when the U.S. West went quiet.

2014/15 Ski Season

Out of all the infamous “Blob” seasons, this one took the crown as the worst yet. California, the Pacific Northwest, Utah, and the U.S. Northern Rockies all tied or broke snowfall records dating back to the brutal winter of ‘76–‘77. Even the “better” zones still clocked in below average. And it wasn’t just skiers who felt the impact. Small businesses took a hit too, with some even forced to close their doors for good.

West Coast (California & Pacific Northwest):

Similar to 2013/14 winter it wasn’t just the lack of snow—it was the elevation rollercoaster. Storms often looked promising but came in warm, dumping rain below 8,000 feet and snow only up high. February’s biggest system turned into a washout for much of the region, and March brought almost nothing—some California resorts saw zero snow. Ironically, the most wintry weather hit in April and May, but by then, the lifts had mostly stopped spinning.

Rockies (Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana):

The season started strong with steady November snow, but after a warm pre-holiday storm gave 2–3 feet, mid-to-late January turned brutally dry. February stayed weak, with snowfall less than half normal in Utah and Colorado. Relief came late February into early March with 2–3 feet from two big storms, but March quickly dried out again. The real surprise? A cold, snowy spring along the I-70 corridor that kept the season alive when it looked done.

Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, Southern Utah):

November through January barely registered any activity. But then—boom! The second half of February delivered one of the Southwest’s best stretches in years. Two major storms unloaded 5–7 feet of snow, transforming what had been a dismal season into something rideable almost overnight. Unfortunately, the party was short-lived. March returned to warm and dry conditions, and most areas didn’t see much action afterward. A few spring storms in April helped cap things off, but with limited operations still running, it didn’t make much of a dent.

Western Canada:

Western Canada’s winter was defined by a frustrating warm pattern—early storms brought solid coverage, but mid-season storms often fell as rain below 7,000 feet, even in the mountains. January was mostly dry, and February’s big system followed suit with wet lows and snow only at higher elevations. March added a modest three feet but couldn’t erase the mid-winter slump. A colder April brought a late-season burst, but by then, the season was winding down.